Brython

Maponos

Maponos: 'the Son' is a Gallo-Brythonic god of youth, hunting and music. His centre of worship was the 'locus Maponi': the Clochmaben Stone in northern Britain. In Culhwch and Olwen, Mabon son of Modron 'Mother', has to be rescued from imprisonment in order for the hunt of Twrch Trwyth to be successful.

A Hymn to Maponos at Midsummer

The sun sails high in a neverdark sky

And Maponos rides the tide of summer

Tall are the grasses grown in the fields

the Breeze sighs through them, singing of summer

The forests adorned with a crown of green

beneath plays the God, in the glades of summer

The harp of Maponos vibrates the air,

and late, in the twilight, still it’s summer

Heron

And Maponos rides the tide of summer

Tall are the grasses grown in the fields

the Breeze sighs through them, singing of summer

The forests adorned with a crown of green

beneath plays the God, in the glades of summer

The harp of Maponos vibrates the air,

and late, in the twilight, still it’s summer

Heron

Maponos, Oengus mac Óc and the Spirit of Poetry

by Heron

The Welsh poet, Henry Vaughan wrote to his cousin, the antiquary John Aubrey, in October 1694, in response to a request that he supply details of any remnants of the druids in Wales. He was presumably looking for evidence of the awenyddion mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis but what Vaughan gives him is something quite different. Here is part of Vaughan’s reply to Aubrey:

“… the antient Bards … communicated nothing of their knowledge, butt by way of tradition: which I suppose to be the reason that we have no account left nor any sort of remains, or other monuments of their learning or way of living. As to the later Bards, you shall have a most curious Account of them.

This vein of poetrie they called Awen, which in their language signifies rapture, or a poetic furore & (in truth) as many of them as I have conversed with are (as I may say) gifted or inspired with it. I was told by a very sober, knowing person (now dead) that in his time, there was a young lad fatherless & motherless, soe very poor that he was forced to beg; butt att last was taken up by a rich man, that kept a great stock of sheep upon the mountains not far from the place where I now dwell who cloathed him & sent him into the mountains to keep his sheep. There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep in which he dreamt, that he saw a beautifull young man with a garland of green leafs upon his head, & an hawk upon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) att last lett the hawk fly att him, which (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Countrey, making songs upon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time."

This might not tell us much about the ‘ancient bards’ but the identity of the young man in a garland of green leaves with the hawk and arrows is of some interest. Maponos has been suggested. But even if we prefer to think of him as a generalised ‘Green Man’ figure, this is a remarkably specific and evocative written record of a pagan spirit of nature, music and inspiration.

In Cormac’s Glossary is a story about a Chief Bard of Ireland in the seventh century called Senchán. He is embarking from Ireland to the Isle of Man with a retinue of bards when “a foul-faced lad (gillie)” called to them from the shore as if he were mad. He is described in groteque detail but in spite of his appearance he is allowed o board.

When they reach the Isle of Man they are accosted by an old woman poet whose whereabouts have been unknown for some time. She challenges Senchán to a rhyme-matching competition but he is unable to match her rhyme so the lad does so instead. She tries again, and again the lad matches her rhyme. They take her back to Ireland with them and then see that the lad is no longer the bedraggled ‘monster’ that he was but “a young hero with golden-yellow hair curlier than the cross-trees of small harps: royal raiment he wore, and his form was the noblest that hath been seen on a human being.” At this point the Irish text changes to Latin for the following two sentences: “He went right-hand-wise round Senchán and his people and then disappeared. It is not, therefore, doubtful that he was the Spirit of Poetry.”

While there are parallels with the story from Vaughan, there are also differences. If we can make the ascription to Oengus mac Óc, the god here does not enter the young shepherd as Maponos does, but actually appears in the guise of a ‘gillie’ of horrible appearance. His true(?) appearance, when he adopts it, is of a noble hero. He is not, as in Vaughan’s story, a hunter with arrows and a hawk though (in a later manuscript version) he has a sword. If the Spirit of Poetry is manifest in Oengus in Ireland, and Maponos in Britain and Gaul, and if these seem to share some characteristics with Apollo according to the Romans, we have a lot to go on in discerning the nature of this god. But gods regarded as ‘equivalent’ by Roman commentators and by mythographers are often more elusive in the forms they take in particular locations.

So we have the Welsh example of a figure clad in green leaves with a quiver full of arrows and a hawk, clearly a hunter who is also able to enter a shepherd and inspire him to write poetry, a figure we can associate with Maponos. And we have in Irish a figure who is transformed from all that is ugly to all that is beautiful and is identified as the spirit of poetry. A figure we can associate with Oengus mac Óc.

Consider Oengus:

"And he was a beautiful young man, with high looks, and his appearance was more beautiful than all beauty, and there were ornaments of gold on his dress; in his hand he held a silver harp with strings of red gold, and the sound of its strings was sweeter than all music under the sky; and over the harp were two birds that seemed to be playing on it. He sat beside me pleasantly and played his sweet music to me, and in the end he foretold things that put drunkenness on my wits."

Now think of Maponos, or Mabon Son of Modron, the divine son, and consider that Maponos was associated with Apollo, that Mabon – in Culhwch and Olwen - emerged from the darkness into the light of life. And consider how god identities might shift. So that Oengus mac Óc might walk the woods of Ireland in a similar guise. And it's not that he is, or he isn't a Sun God; not that he is or he isn't a Vegetation God ... and though he is certainly the god that plays the sweetest tune. He is the Awen, youth transforming itself to the fullness of age but remaining ever young, the inspiration and the expiration of the Muse and he plays his music in what seems like an endless day.

“… the antient Bards … communicated nothing of their knowledge, butt by way of tradition: which I suppose to be the reason that we have no account left nor any sort of remains, or other monuments of their learning or way of living. As to the later Bards, you shall have a most curious Account of them.

This vein of poetrie they called Awen, which in their language signifies rapture, or a poetic furore & (in truth) as many of them as I have conversed with are (as I may say) gifted or inspired with it. I was told by a very sober, knowing person (now dead) that in his time, there was a young lad fatherless & motherless, soe very poor that he was forced to beg; butt att last was taken up by a rich man, that kept a great stock of sheep upon the mountains not far from the place where I now dwell who cloathed him & sent him into the mountains to keep his sheep. There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep in which he dreamt, that he saw a beautifull young man with a garland of green leafs upon his head, & an hawk upon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) att last lett the hawk fly att him, which (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Countrey, making songs upon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time."

This might not tell us much about the ‘ancient bards’ but the identity of the young man in a garland of green leaves with the hawk and arrows is of some interest. Maponos has been suggested. But even if we prefer to think of him as a generalised ‘Green Man’ figure, this is a remarkably specific and evocative written record of a pagan spirit of nature, music and inspiration.

In Cormac’s Glossary is a story about a Chief Bard of Ireland in the seventh century called Senchán. He is embarking from Ireland to the Isle of Man with a retinue of bards when “a foul-faced lad (gillie)” called to them from the shore as if he were mad. He is described in groteque detail but in spite of his appearance he is allowed o board.

When they reach the Isle of Man they are accosted by an old woman poet whose whereabouts have been unknown for some time. She challenges Senchán to a rhyme-matching competition but he is unable to match her rhyme so the lad does so instead. She tries again, and again the lad matches her rhyme. They take her back to Ireland with them and then see that the lad is no longer the bedraggled ‘monster’ that he was but “a young hero with golden-yellow hair curlier than the cross-trees of small harps: royal raiment he wore, and his form was the noblest that hath been seen on a human being.” At this point the Irish text changes to Latin for the following two sentences: “He went right-hand-wise round Senchán and his people and then disappeared. It is not, therefore, doubtful that he was the Spirit of Poetry.”

While there are parallels with the story from Vaughan, there are also differences. If we can make the ascription to Oengus mac Óc, the god here does not enter the young shepherd as Maponos does, but actually appears in the guise of a ‘gillie’ of horrible appearance. His true(?) appearance, when he adopts it, is of a noble hero. He is not, as in Vaughan’s story, a hunter with arrows and a hawk though (in a later manuscript version) he has a sword. If the Spirit of Poetry is manifest in Oengus in Ireland, and Maponos in Britain and Gaul, and if these seem to share some characteristics with Apollo according to the Romans, we have a lot to go on in discerning the nature of this god. But gods regarded as ‘equivalent’ by Roman commentators and by mythographers are often more elusive in the forms they take in particular locations.

So we have the Welsh example of a figure clad in green leaves with a quiver full of arrows and a hawk, clearly a hunter who is also able to enter a shepherd and inspire him to write poetry, a figure we can associate with Maponos. And we have in Irish a figure who is transformed from all that is ugly to all that is beautiful and is identified as the spirit of poetry. A figure we can associate with Oengus mac Óc.

Consider Oengus:

"And he was a beautiful young man, with high looks, and his appearance was more beautiful than all beauty, and there were ornaments of gold on his dress; in his hand he held a silver harp with strings of red gold, and the sound of its strings was sweeter than all music under the sky; and over the harp were two birds that seemed to be playing on it. He sat beside me pleasantly and played his sweet music to me, and in the end he foretold things that put drunkenness on my wits."

Now think of Maponos, or Mabon Son of Modron, the divine son, and consider that Maponos was associated with Apollo, that Mabon – in Culhwch and Olwen - emerged from the darkness into the light of life. And consider how god identities might shift. So that Oengus mac Óc might walk the woods of Ireland in a similar guise. And it's not that he is, or he isn't a Sun God; not that he is or he isn't a Vegetation God ... and though he is certainly the god that plays the sweetest tune. He is the Awen, youth transforming itself to the fullness of age but remaining ever young, the inspiration and the expiration of the Muse and he plays his music in what seems like an endless day.

Maponus

by Lorna

Maponus is a god of youth, music and hunting who is known from dedications from the Romano-British period in the North of Britain and Gaul. His name, which is Gallo-Brythonic, means ‘the son.’ Of the five dedications, which occur in Northumbria, Cumberland and here in Lancashire at Ribchester, four equate Maponus with Apollo , a Roman god associated with music, healing, prophecy, archery and the sun. In the Pythagorean tradition, the British Isles were seen as the home of the ‘Hyperborean Apollo,’ a sign of the longevity of Maponus’ worship and reputation here.

The dedication at Ribchester (241CE), which can be found in the museum, reads: ‘To the holy god Apollo Maponus, and for the health of our Lord (i.e. the Emperor) and the unit of the Gordian Sarmartian Horse at Bremetenacum, Aelius Antonius, centurion of the Sixth Legion, the Victrix (Victress) from Melitanis (?) praepositus (provost) of the unit and the region, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow .’

Within Ribchester’s museum stands a pedestal, which is believed to have ‘carried four figures in relief . On one side is Apollo, clad in a cloak and Phrygian cap, wearing a quiver and resting on his lyre. The side which possibly carried a relief of Maponus has been defaced. On another side are two female figures, whose identity and roles have been interpreted differently. Nick Ford interprets the relief to depict the genius loci of Ribchester making an offering to Belisama, the goddess of the Ribble.

Anne Ross believes the figures might be Maponus’ mother Modron and a native hunter goddess equated with Diana (Diana’s Greek counterpart was Artemis, Apollo’s twin sister). Anne’s theory stems from the identification of Maponus with Mabon, son of Modron in Welsh myth. Modron means ‘mother.’ It is likely she was known earlier as Matrona. An altar from Ribchester bears an inscription to ‘all the mother goddesses’ (the deae matrones) and another, similar, has been found in Kirkham .

Maponus has strong associations with the village of Lochmaben in Dumfrieshire. A folk tale from this area tells of ‘the harper of Lochmaben’ who ‘goes to London and steals away King Henry’s brown mare’. Close to the village lies the Clochmabenstone, a tribal gathering place near Gretna where runaway lovers were married . It stands beside the Solway, close to the estuary. Anne Ross suggests this may have been Maponus’ ‘fanum’ (shrine or sacred precinct), which features as the ‘locus Maponi’ of the Ravenna cosmology. The promonotory at Lochmaben may have been his temenos . Another place named after him is ‘Ruabon, the Hill of Mabon, below Wrexham’ on the Severn . Guy Ragland Philips identifies ‘Mapon’ with the spirit known as the son of the rocks, at Brimham Rocks in Yorkshire’.

Most of these places are connected with water and / or stone. A relief from Whitley castle in Cumbria of a ‘native radiate god’ suggests that like Apollo Maponus is connected with the sun. The associations of Maponus with stone, water and the sun recur in the story of the rescue of Mabon in ‘How Culwch won Olwen’ in The Mabinogion.

Before moving on, I’d like to pause to address the question of whether Maponus and Mabon are the same god. The historian Ronald Hutton believes there is no proof to identify figures from the Welsh myths with earlier gods known from archaeological evidence. This is the starting point I usually set out from. However through connecting with both Maponus and Mabon, I have found that although my connection with Maponus feels stronger, their presence feels the same. This suggests to me they are the same god / divine figure, seen and named at different times by different cultures (i.e. Romano-British and Medieval Welsh).

In ‘How Culwch won Olwen’ there are several references to ‘the North,’ suggesting some episodes may have originated from ‘The Old North,’ an area which between the 5th and 7th covered Northern Britain and Southern Scotland and was divided between a number of petty kings.

Mabon’s rescue takes place within the context of Culwch’s task to win Olwen by hunting down the King of Boars, Twrch Trwth. To hunt the boar, Culwch requires Mabon’s aid. However, Mabon was stolen when three nights old from ‘between his mother and the wall… No one knows where he is, nor what state he’s in, whether dead or alive.’ The search for Mabon takes Arthur’s men, via the story of the ‘Oldest Animals’ (a blackbird, stag, owl, eagle and salmon) through the present day Wirral, Cheshire and parts of Wales to Gloucester on the river Severn. Mabon is found imprisoned lamenting in a ‘house of stone.’ Whilst Arthur and his men fight, Cai tears down the walls and rescues Mabon aboard the back of the salmon. With the dog Drudwyn (fierce white) and steed- Gwyn Myngddwn (‘white dark mane’) who is ‘swift as a wave’ Mabon joins the hunt for Twrch Trwth, riding into the Hafren to take the razor from between the boar’s ears . It is possible to read from this traces of an older myth of the rescue of the sun from its house of stone in the earth, at dawn appearing shining in the river.

A number of tales / poems connect Mabon and Modron to the Kingdom of Rheged, which covered Cumbria, Lancashire and northern Cheshire. In one story Urien Rheged travels to ‘the Ford of Barking’ in Llanferes, where he meets Modron, ‘daughter of Avallach’ washing in the ford. He sleeps with her and she conceives his children, Owein and Morfudd . In The Black Book Caermarthen, Mabon appears as ‘the son of Myrdon the servant of Uther Pendragon’ . References to Mabon also appear in The Book of Taliesin (who was Urien Rheged’s Bard). ‘Will greet Mabon from another country / A battle, when Owain defends the cattle of his country.’ ‘Against Mabon without corpses they would not go.’ ‘The country of Mabon is pierced with destructive slaughter.’ ‘When was caused the battle of the king, sovereign, prince / Very wild will be the kine before Mabon . However it is unclear whether Mabon is himself taking part in the battle, whether Mabon is being used as a title for Owain ‘the son,’ or whether Mabon is referred to as a location.

In Brigantia, Guy Ragland Phillips mentions a ‘written charm’ found at a Farmhouse at Oxenhope in 1934 beginning ‘Ominas X Laudet X Mapon.’ He translates this as ‘everybody praises Mapon.’ When Ross Nichols and Gerald Gardner invented to the pagan wheel of the year in the 1950’s the autumn equinox was dedicated to Mabon, showing the continuity of his influence into the twenty first century. His largest festival takes place at Thornborough Henge . With the number of pagans in England and Wales increasing from 42K in 2001 to 82K in 2011, my guess is that the following of our native god of youth, music and happiness will grow and continue for many years to come.

Originally published online at From Peneverdant

(1) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p87.

(2) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974) p463- 4

(3) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p179.

(4) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p87.

(5) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974) p276

(6) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p88

(7) Ibid. p277

(8) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p86.

(9) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974), p270.

(10) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p178.

(11) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, p458

(12) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p178.

(13) Guy Ragland Phillips, Brigantia: A Mysteriography, (1976), p128

(14) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974), p477

(15) Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, p 198 – 212

(16) http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/modron.html

(17) Ed. William F. Skene, ‘The Black Book of Caermarthen XXXI’. ‘Pa Gur. Arthur and the Porter.’ The Four Ancient Books of Wales, (1868), p179.

(18) Ibid. ‘The Book of Taliessin XVIII’ ‘A Rumour had come to from Calchvynd’ p277.

(19) http://www.celebratemabon.co.uk/

The dedication at Ribchester (241CE), which can be found in the museum, reads: ‘To the holy god Apollo Maponus, and for the health of our Lord (i.e. the Emperor) and the unit of the Gordian Sarmartian Horse at Bremetenacum, Aelius Antonius, centurion of the Sixth Legion, the Victrix (Victress) from Melitanis (?) praepositus (provost) of the unit and the region, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow .’

Within Ribchester’s museum stands a pedestal, which is believed to have ‘carried four figures in relief . On one side is Apollo, clad in a cloak and Phrygian cap, wearing a quiver and resting on his lyre. The side which possibly carried a relief of Maponus has been defaced. On another side are two female figures, whose identity and roles have been interpreted differently. Nick Ford interprets the relief to depict the genius loci of Ribchester making an offering to Belisama, the goddess of the Ribble.

Anne Ross believes the figures might be Maponus’ mother Modron and a native hunter goddess equated with Diana (Diana’s Greek counterpart was Artemis, Apollo’s twin sister). Anne’s theory stems from the identification of Maponus with Mabon, son of Modron in Welsh myth. Modron means ‘mother.’ It is likely she was known earlier as Matrona. An altar from Ribchester bears an inscription to ‘all the mother goddesses’ (the deae matrones) and another, similar, has been found in Kirkham .

Maponus has strong associations with the village of Lochmaben in Dumfrieshire. A folk tale from this area tells of ‘the harper of Lochmaben’ who ‘goes to London and steals away King Henry’s brown mare’. Close to the village lies the Clochmabenstone, a tribal gathering place near Gretna where runaway lovers were married . It stands beside the Solway, close to the estuary. Anne Ross suggests this may have been Maponus’ ‘fanum’ (shrine or sacred precinct), which features as the ‘locus Maponi’ of the Ravenna cosmology. The promonotory at Lochmaben may have been his temenos . Another place named after him is ‘Ruabon, the Hill of Mabon, below Wrexham’ on the Severn . Guy Ragland Philips identifies ‘Mapon’ with the spirit known as the son of the rocks, at Brimham Rocks in Yorkshire’.

Most of these places are connected with water and / or stone. A relief from Whitley castle in Cumbria of a ‘native radiate god’ suggests that like Apollo Maponus is connected with the sun. The associations of Maponus with stone, water and the sun recur in the story of the rescue of Mabon in ‘How Culwch won Olwen’ in The Mabinogion.

Before moving on, I’d like to pause to address the question of whether Maponus and Mabon are the same god. The historian Ronald Hutton believes there is no proof to identify figures from the Welsh myths with earlier gods known from archaeological evidence. This is the starting point I usually set out from. However through connecting with both Maponus and Mabon, I have found that although my connection with Maponus feels stronger, their presence feels the same. This suggests to me they are the same god / divine figure, seen and named at different times by different cultures (i.e. Romano-British and Medieval Welsh).

In ‘How Culwch won Olwen’ there are several references to ‘the North,’ suggesting some episodes may have originated from ‘The Old North,’ an area which between the 5th and 7th covered Northern Britain and Southern Scotland and was divided between a number of petty kings.

Mabon’s rescue takes place within the context of Culwch’s task to win Olwen by hunting down the King of Boars, Twrch Trwth. To hunt the boar, Culwch requires Mabon’s aid. However, Mabon was stolen when three nights old from ‘between his mother and the wall… No one knows where he is, nor what state he’s in, whether dead or alive.’ The search for Mabon takes Arthur’s men, via the story of the ‘Oldest Animals’ (a blackbird, stag, owl, eagle and salmon) through the present day Wirral, Cheshire and parts of Wales to Gloucester on the river Severn. Mabon is found imprisoned lamenting in a ‘house of stone.’ Whilst Arthur and his men fight, Cai tears down the walls and rescues Mabon aboard the back of the salmon. With the dog Drudwyn (fierce white) and steed- Gwyn Myngddwn (‘white dark mane’) who is ‘swift as a wave’ Mabon joins the hunt for Twrch Trwth, riding into the Hafren to take the razor from between the boar’s ears . It is possible to read from this traces of an older myth of the rescue of the sun from its house of stone in the earth, at dawn appearing shining in the river.

A number of tales / poems connect Mabon and Modron to the Kingdom of Rheged, which covered Cumbria, Lancashire and northern Cheshire. In one story Urien Rheged travels to ‘the Ford of Barking’ in Llanferes, where he meets Modron, ‘daughter of Avallach’ washing in the ford. He sleeps with her and she conceives his children, Owein and Morfudd . In The Black Book Caermarthen, Mabon appears as ‘the son of Myrdon the servant of Uther Pendragon’ . References to Mabon also appear in The Book of Taliesin (who was Urien Rheged’s Bard). ‘Will greet Mabon from another country / A battle, when Owain defends the cattle of his country.’ ‘Against Mabon without corpses they would not go.’ ‘The country of Mabon is pierced with destructive slaughter.’ ‘When was caused the battle of the king, sovereign, prince / Very wild will be the kine before Mabon . However it is unclear whether Mabon is himself taking part in the battle, whether Mabon is being used as a title for Owain ‘the son,’ or whether Mabon is referred to as a location.

In Brigantia, Guy Ragland Phillips mentions a ‘written charm’ found at a Farmhouse at Oxenhope in 1934 beginning ‘Ominas X Laudet X Mapon.’ He translates this as ‘everybody praises Mapon.’ When Ross Nichols and Gerald Gardner invented to the pagan wheel of the year in the 1950’s the autumn equinox was dedicated to Mabon, showing the continuity of his influence into the twenty first century. His largest festival takes place at Thornborough Henge . With the number of pagans in England and Wales increasing from 42K in 2001 to 82K in 2011, my guess is that the following of our native god of youth, music and happiness will grow and continue for many years to come.

Originally published online at From Peneverdant

(1) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p87.

(2) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974) p463- 4

(3) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p179.

(4) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p87.

(5) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974) p276

(6) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p88

(7) Ibid. p277

(8) Nick Ford, ‘Ribchester (Bremetenacum Veteranorum): Place of the Roaring Water’ Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, ed. Linda Sever, 2010, p86.

(9) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974), p270.

(10) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p178.

(11) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, p458

(12) Caitlin Matthews, Mabon and the Guardians of Celtic Britain, (2002), p178.

(13) Guy Ragland Phillips, Brigantia: A Mysteriography, (1976), p128

(14) Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, (1974), p477

(15) Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, p 198 – 212

(16) http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/modron.html

(17) Ed. William F. Skene, ‘The Black Book of Caermarthen XXXI’. ‘Pa Gur. Arthur and the Porter.’ The Four Ancient Books of Wales, (1868), p179.

(18) Ibid. ‘The Book of Taliessin XVIII’ ‘A Rumour had come to from Calchvynd’ p277.

(19) http://www.celebratemabon.co.uk/

MAPONOS

by Greg

Gogyfarch Vabon o arall vro

Call upon Mabon from the Other Realm

(Book of Taliesin : 38)

Call upon Mabon from the Other Realm

(Book of Taliesin : 38)

|

Divine Son of Divine Mother, taken at three nights old into the Otherworld but brought back out of the darkness into the light of this world. Playing the Harp of Time he brings the music of the world out of silence into the sights and sounds of Summer. His is the bright step into the eternal present of Now, the act of Being, the vitality of youth grown to manhood. He may come as a hunter decked in leaves with a sheaf of arrows to inspire a bard, as the Welsh poet Henry Vaughan relates.

|

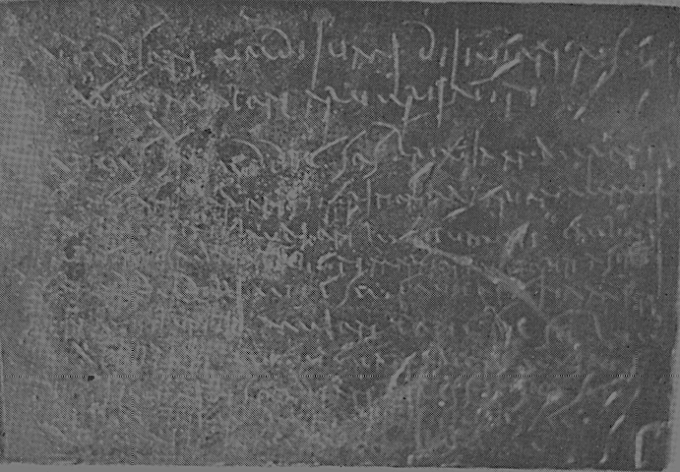

Iron Age coin from Sussex showing a horse and a lyre

|

In the tale of Culhwch and Olwen he is Mabon, released from the dungeon of Caer Loyw to join Arthur and his men to hunt Twrch Trwyth. He is simultaneously the Divine Youth, the ever-young, and one whom only the most ancient of the ancient creatures of the world can remember. In the Mabinogi tales he is Pryderi, taken from his mother Rhiannon as a baby and brought back by Teyrnon, then taken again as an adult and brought back by Manawydan. These stories enact on the plane of human narrative the mythology of Maponos moving between Time and Not-Time, between Light and Darkness, between Music and Silence, between Thisworld and Annwn.

He is the Son of the Horse Goddess who plucks the strings the harp or the lyre as he twangs the string of his bow to bring inspiration or show the way for a seeker after the mysteries. As Mabon he takes the razor from between the ears of the boar Twrch Trwyth for the giant Ysbadadden to be shaved so Culhwch can wed Olwen. As Pryderi he hunts a shining white boar which leads him into an otherworld caer. Manawydan - 'wise of counsel' - does not follow but finds a way to bring him back. These then reflect the rites of departure and beckoning as we welcome him once more onto the path of discovery, of life, and all its mysteries which are his to reveal.

So he may walk the plains of Summer in our world, bringing it alive with each vibration of the strings of his harp, or he may be sought for through a seer, an awenydd or one who walks the paths between the worlds. An inscription in Gaulish found in a sacred spring at Chamelières calls upon him thus:

Maponos of the Deep, Great God

I come to you with this plea:

Bring the powers of the Otherworld

To inspire those who are before thee.

He is the Son of the Horse Goddess who plucks the strings the harp or the lyre as he twangs the string of his bow to bring inspiration or show the way for a seeker after the mysteries. As Mabon he takes the razor from between the ears of the boar Twrch Trwyth for the giant Ysbadadden to be shaved so Culhwch can wed Olwen. As Pryderi he hunts a shining white boar which leads him into an otherworld caer. Manawydan - 'wise of counsel' - does not follow but finds a way to bring him back. These then reflect the rites of departure and beckoning as we welcome him once more onto the path of discovery, of life, and all its mysteries which are his to reveal.

So he may walk the plains of Summer in our world, bringing it alive with each vibration of the strings of his harp, or he may be sought for through a seer, an awenydd or one who walks the paths between the worlds. An inscription in Gaulish found in a sacred spring at Chamelières calls upon him thus:

Maponos of the Deep, Great God

I come to you with this plea:

Bring the powers of the Otherworld

To inspire those who are before thee.

Lead tablet with Gaulish inscription to MAPONOS from Chamelières

He may come, once again, into the world to inspire us, to touch the strings of his harp riding the particles of silence behind him as they touch the waves of sound that rush through the world like the song of the Birds of Rhiannon over the waves of the sea and on every zephyr that touches the trees of the world. So we shape these words to call upon him:

Maponos : we sense your call

From the silence of the Deeps beyond our world

Maponos : Matrona remembers her child

Whom we bring to her with this wish for your coming

Maponos : You are the seed of Summer

Dwelling in darkness and springing into light

Maponos : we hear your harp-song

As the Sun rides high in the Midsummer sky.

The Gaulish text of the Chamelières Tablet is given in The Celtic Heroic Age ed. John Koch & John Carey (Aberysywyth, 2003) where a word by word interpretation is also given. The four-line verse above is based on that.

Other References:

Culhwch ac Olwen : Rachel Bromwich a Simon Evans (Cardiff, 1997)

Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi : Ifor Williams (Cardiff, 1978)

Maponos : we sense your call

From the silence of the Deeps beyond our world

Maponos : Matrona remembers her child

Whom we bring to her with this wish for your coming

Maponos : You are the seed of Summer

Dwelling in darkness and springing into light

Maponos : we hear your harp-song

As the Sun rides high in the Midsummer sky.

The Gaulish text of the Chamelières Tablet is given in The Celtic Heroic Age ed. John Koch & John Carey (Aberysywyth, 2003) where a word by word interpretation is also given. The four-line verse above is based on that.

Other References:

Culhwch ac Olwen : Rachel Bromwich a Simon Evans (Cardiff, 1997)

Pedeir Keinc y Mabinogi : Ifor Williams (Cardiff, 1978)

Proudly powered by Weebly