Brython

Yr Haf - Summer

As crops and fruits ripen beneath the summer sun, the land is at its most fertile we honour the spirits of the land and deities of this season

May/June: Bel and Belisama

Festival honouring Bel as god of fire and sun and Belisama as goddess of shining waters and high summer.

Summer Solstice

Festival celebrating the longest day and shortest night and the bounty of summer.

June: Maponos

Festival for Maponos, god of youth, music and hunting

Festival honouring Bel as god of fire and sun and Belisama as goddess of shining waters and high summer.

Summer Solstice

Festival celebrating the longest day and shortest night and the bounty of summer.

June: Maponos

Festival for Maponos, god of youth, music and hunting

Bel and Belisama

The name ‘Bel’ means ‘Bright’, ‘Shining’ or ‘Mighty’ and is attested across Celtic speaking countries from northern Italy and Austria to Gaul and Britain in many variants: Bel, Belenus, Belenos, Belinos, Belinu, and Bellinus. Here in Lancashire I know him as Bel and suspect he gives his name to Belthorn and Belgrave. ‘Belisama’ means ‘Most Bright/Shining/Mighty One’ and also translates as ‘Summer Bright’. She was venerated in Gaul and Ptolemy labels the Ribble estuary in Lancashire ‘Belisama Aest’. Nick Ford suggests the name of the Ribble derives from Riga ‘Queen’ Belisama (Ri…Bel).

Within my locality, Bel and Belisama are constant presences as sun god and goddess of the Ribble’s shining waters. However, their presence feels strongest from Calan Mai/Beltane to the Summer Solstice. Etymological and historical links show their associations with Beltane.

Beltane is a Gaelic festival first attested in the Irish glossary Sanas Chormaic. Under ‘Beltane’ both texts have ‘“lucky fire”, ie. two fires which Druids used to make great incantations, and they used to bring the cattle against the diseases of each year to those fires’. In the margins under ‘Bil’: ‘from Bial ie. an idol god, from which Beltine ie. fire of Bel’. Belfires are also recorded in Scotland, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Cumbria. In Great Singleton and Lancaster in Lancashire there was a triennial cattle fair on May Day called Beltancu. This shares similarities with the treth-Calan-Mai in Wales, where a tribute of cows was paid to King Maelgwn of Gwynedd in the 6thC. The bondsmen of Great Singleton gave four cows to their lord’s stock and Skorton and Overton paid cowgeld. I imagine it was around this time the cows from my home town of Penwortham were once moved to their summer pastures in Brindle. Lancashire folklorists John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson claim ‘the heathen cult’ of Bel ‘lingered’ in the Fylde area. ‘From the great heaps of stones on eminences, called Cairns or Toot-hills*… and the Belenian eminences, whereon was worshipped Bel… the grand sacred fires of the Bel-Tine flamed thrice a year… on the eve of May-Day, on Midsummer Eve, and on the eve of the 1st November.’

They also record that ‘Beltains’ or ‘Teanlas’ were lit beside the Ribble on Halloween and ‘cakes as the Jews are said to have made’ are baked ‘in honour of the Queen of Heaven… Belisama.’ It seems possible similar rites took place on Beltane too.

The baking of oatcakes on Beltane is certainly recorded in other areas. At a Bel-tein in the Highlands, a large caudle was baked and shared. Nine knobs were broken off as offerings to the preservers of the flocks and herds and to the animals. In Perthshire, the person who received a charred piece of the oat cake was seen as devoted to Baal (Bel) and made to jump through the fire three times. Similar rites are recorded in Caithness and Derbyshire. Anne Ross says this may echo earlier traditions of human sacrifice.

I’ve celebrated Bel and Belisama’s presence in the land at this time of year in various ways. A few years ago, I organised a ritual for them with UCLan Pagan Society. This involved two processions of people circling the room singing fire and water chants, then leaping over a bowl of water with a candle in it to a chant gifted me whilst walking beside the Ribble:

Within my locality, Bel and Belisama are constant presences as sun god and goddess of the Ribble’s shining waters. However, their presence feels strongest from Calan Mai/Beltane to the Summer Solstice. Etymological and historical links show their associations with Beltane.

Beltane is a Gaelic festival first attested in the Irish glossary Sanas Chormaic. Under ‘Beltane’ both texts have ‘“lucky fire”, ie. two fires which Druids used to make great incantations, and they used to bring the cattle against the diseases of each year to those fires’. In the margins under ‘Bil’: ‘from Bial ie. an idol god, from which Beltine ie. fire of Bel’. Belfires are also recorded in Scotland, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Cumbria. In Great Singleton and Lancaster in Lancashire there was a triennial cattle fair on May Day called Beltancu. This shares similarities with the treth-Calan-Mai in Wales, where a tribute of cows was paid to King Maelgwn of Gwynedd in the 6thC. The bondsmen of Great Singleton gave four cows to their lord’s stock and Skorton and Overton paid cowgeld. I imagine it was around this time the cows from my home town of Penwortham were once moved to their summer pastures in Brindle. Lancashire folklorists John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson claim ‘the heathen cult’ of Bel ‘lingered’ in the Fylde area. ‘From the great heaps of stones on eminences, called Cairns or Toot-hills*… and the Belenian eminences, whereon was worshipped Bel… the grand sacred fires of the Bel-Tine flamed thrice a year… on the eve of May-Day, on Midsummer Eve, and on the eve of the 1st November.’

They also record that ‘Beltains’ or ‘Teanlas’ were lit beside the Ribble on Halloween and ‘cakes as the Jews are said to have made’ are baked ‘in honour of the Queen of Heaven… Belisama.’ It seems possible similar rites took place on Beltane too.

The baking of oatcakes on Beltane is certainly recorded in other areas. At a Bel-tein in the Highlands, a large caudle was baked and shared. Nine knobs were broken off as offerings to the preservers of the flocks and herds and to the animals. In Perthshire, the person who received a charred piece of the oat cake was seen as devoted to Baal (Bel) and made to jump through the fire three times. Similar rites are recorded in Caithness and Derbyshire. Anne Ross says this may echo earlier traditions of human sacrifice.

I’ve celebrated Bel and Belisama’s presence in the land at this time of year in various ways. A few years ago, I organised a ritual for them with UCLan Pagan Society. This involved two processions of people circling the room singing fire and water chants, then leaping over a bowl of water with a candle in it to a chant gifted me whilst walking beside the Ribble:

Bel and Belisama

join together

fire on water

sun on the river.

join together

fire on water

sun on the river.

This was followed by readings of poems and stories, then feasting, and libations outside the building at the end. I’ve also read my poem ‘Summer Bright’ for Belisama in public.

This year, I experienced a magical moment on the hot second week of May without having made any set plans. I went for a bike ride from Penwortham toward Brockholes and stopped beside the Ribble where the sun was dancing from the sparkling water. Downriver I noticed a group of cows had descended into the water to drink. I sat for a while, counting swallows, losing myself in the play of light on ripples, the song of the wind. When looked back, the cows were standing in a semi-circle around me: they seemed to have approached without a sound!

On the next sunny day I baked an oatcake and took it to where the cows had descended into the Ribble. As the sun broke through the clouds to shine on the river I offered it to Bel, Belisama, the keepers of cows, the cows, a nearby heron, the swallows and gulls.

*According to Harland and Wilkinson ‘the hills dedicated to the worship of the Celtic god Tot, or Teut, or Teutates’.

SOURCES

Anne Ross and Don Robins, The Life and Death of a Druid Prince, (Summit Books, 1989)

James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, (OUP, 1998)

John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore, (Kessinger, 1867)

Ronald Cunliffe-Shawe, Men of the North, (Leyland Printing Co, 1970)

Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun, (OUP, 1996)

This year, I experienced a magical moment on the hot second week of May without having made any set plans. I went for a bike ride from Penwortham toward Brockholes and stopped beside the Ribble where the sun was dancing from the sparkling water. Downriver I noticed a group of cows had descended into the water to drink. I sat for a while, counting swallows, losing myself in the play of light on ripples, the song of the wind. When looked back, the cows were standing in a semi-circle around me: they seemed to have approached without a sound!

On the next sunny day I baked an oatcake and took it to where the cows had descended into the Ribble. As the sun broke through the clouds to shine on the river I offered it to Bel, Belisama, the keepers of cows, the cows, a nearby heron, the swallows and gulls.

*According to Harland and Wilkinson ‘the hills dedicated to the worship of the Celtic god Tot, or Teut, or Teutates’.

SOURCES

Anne Ross and Don Robins, The Life and Death of a Druid Prince, (Summit Books, 1989)

James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, (OUP, 1998)

John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson, Lancashire Folklore, (Kessinger, 1867)

Ronald Cunliffe-Shawe, Men of the North, (Leyland Printing Co, 1970)

Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun, (OUP, 1996)

Maponos and Midsummer

This will be an exploration matching personal revelation with historical research. That is, it sketches part of the process that a polytheist working in a particular tradition must be involved in to match present experience with what can be recovered from a remote time when the tradition was vibrant: finding the old way of saying and making it new.

Maponos is being discussed now because we have placed him in the season of Midsummer for his festival and his remembrance. Gods cannot be fixed only to particular seasons but their nature can seem to fit certain times of year when their particular qualities are most apparent. So why now? Maponos is the Brythonic, and Gaulish, form (Maponus in Latin) of the name which became Mabon in the medieval Welsh tales. So Mabon son of Modron in the tale Culhwch and Olwen is Maponos son of Matrona, or ‘Divine Son of Divine Mother’. In that tale he is released from a dungeon by the River Severn at Caerloyw, or the Roman fort of Glevum (Gloucester). He is discovered there when the Salmon – one of the oldest living creatures of the world – leads Arthur’s men there to besiege the fort while Cei and Bedwyr rescue him. So he is brought out of the darkness into the light. Of Mabon, the giant Ysbaddaden says that he “was taken from his mother when three nights old” which links him with Pryderi who was similarly snatched from his mother Rhiannon (from *Rigantona or ‘Divine Queen’) shortly after his birth and brought back from obscurity as a grown boy into the light of his father’s court by Teyrnon (from *Tigernonos, or ‘Divine Lord’). So Mabon or Maponos is the divine youth, like Aengus mac Oc in the Irish tradition, and was linked to Apollo by the Romans. His story in mythological terms is of youth coming of age, of Spring opening to Summer, of the long summer days when the Sun rises early and sets late, bringing vibrant life as everything is at the peak of new growth and the music of the spheres plays through the luxuriant growth of grassy meadows and leafy woods as he comes as a piper or a harpist, as a huntsman or a woodsman, as weaver of the enchantment of long Midsummer days and the twilight of short Midsummer nights.

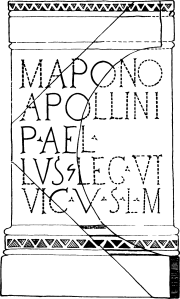

Some of the Brythonic forms of the names given above are marked with an asterisk to show that the original form is not found in any surviving records. But Maponos is recorded in several places from ancient times both in Britain and in Gaul:

He is, therefore well attested both in ancient tradition, in the medieval tales (both directly as Mabon and in analogues such as Pryderi) and in other reflexes some oblique, some less so, where his character, whether named or not, shines through figures of folklore, story and anecdote. One such is the story told by Henry Vaughan in the 17th century about a shepherd lad: “There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep in which he dreamt, that he saw a beautiful young man with a garland of green leafs upon his head, & an hawk upon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) att last lett the hawk fly att him, which (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Countrey, making songs upon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time.”

So Maponos, is the Divine Son, marked by matrilineal descent from the Divine Mother, musician and harper in his different aspects and Mabon – in Culhwch and Olwen, – is released from his dark dungeon to join the hunt for Twrch Trwyth and so takes from the King of boars one of the tokens from between his ears which is required for Culhwch to wed Olwen. The giant, Olwen’s father, says that the hunt for the boar cannot take place without him, and so neither can the wedding of Culhwch (himself a type of the divine boy coming of age) to Olwen (herself a type of the divine girl who awaits him). These two also grow into the light of life. So it is Maponos at Midsummer when the Sun rides high who both partakes in and blesses the wedding feast, the Master Magician fluidly inhabiting both roles. Such is the nature of myth. It’s not that he is, or he isn’t a Sun God; not that he is or he isn’t a Vegetation God … and though he is certainly the god that plays the sweetest tune, he doesn’t ask us to judge but to listen and to learn. The story that Apollo and Pan had a competition as to who was the better musician, a context won by Apollo, has been represented as the god competing with his older self. The Irish writer James Stephens made good use of this idea in his novel The Crock of Gold, in which Pan comes to Ireland and competes with Aengus Og. There is something fundamental here in the opposition of the Woodland Piper with the Muse of Song ; of the Hunter with his arrows and the Spirit of Poetry with his lyre; of the God of the Wild Places with the Master of the Revels. Maponos encompasses them all. He is the Awen, the spirit of Summer, youth transforming itself to awareness and remaining ever young, the inspiration and the expiration of the Muse and he plays his music in what seems like an endless day. His speech is not prose, but poetry; the sense of his song is the Summer

Maponos is being discussed now because we have placed him in the season of Midsummer for his festival and his remembrance. Gods cannot be fixed only to particular seasons but their nature can seem to fit certain times of year when their particular qualities are most apparent. So why now? Maponos is the Brythonic, and Gaulish, form (Maponus in Latin) of the name which became Mabon in the medieval Welsh tales. So Mabon son of Modron in the tale Culhwch and Olwen is Maponos son of Matrona, or ‘Divine Son of Divine Mother’. In that tale he is released from a dungeon by the River Severn at Caerloyw, or the Roman fort of Glevum (Gloucester). He is discovered there when the Salmon – one of the oldest living creatures of the world – leads Arthur’s men there to besiege the fort while Cei and Bedwyr rescue him. So he is brought out of the darkness into the light. Of Mabon, the giant Ysbaddaden says that he “was taken from his mother when three nights old” which links him with Pryderi who was similarly snatched from his mother Rhiannon (from *Rigantona or ‘Divine Queen’) shortly after his birth and brought back from obscurity as a grown boy into the light of his father’s court by Teyrnon (from *Tigernonos, or ‘Divine Lord’). So Mabon or Maponos is the divine youth, like Aengus mac Oc in the Irish tradition, and was linked to Apollo by the Romans. His story in mythological terms is of youth coming of age, of Spring opening to Summer, of the long summer days when the Sun rises early and sets late, bringing vibrant life as everything is at the peak of new growth and the music of the spheres plays through the luxuriant growth of grassy meadows and leafy woods as he comes as a piper or a harpist, as a huntsman or a woodsman, as weaver of the enchantment of long Midsummer days and the twilight of short Midsummer nights.

Some of the Brythonic forms of the names given above are marked with an asterisk to show that the original form is not found in any surviving records. But Maponos is recorded in several places from ancient times both in Britain and in Gaul:

- There is a crescent-shaped silver plaque inscribed ‘DEO MAPONO’ from Vindolanda

- There are dedications to ‘Apollo Maponus’ from Hadrians Wall and elsewhere in Britain

- The Ravenna Cosmography refers to a ‘Locus Maponi’ or centre of his worship at Loch Maben in S.W. Scotland and the nearby Clochmaben Stone remembers him.

- A medieval charter in Gaul records De Mabono fonte suggesting a possible former location for his worship at a sacred spring

He is, therefore well attested both in ancient tradition, in the medieval tales (both directly as Mabon and in analogues such as Pryderi) and in other reflexes some oblique, some less so, where his character, whether named or not, shines through figures of folklore, story and anecdote. One such is the story told by Henry Vaughan in the 17th century about a shepherd lad: “There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep in which he dreamt, that he saw a beautiful young man with a garland of green leafs upon his head, & an hawk upon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) att last lett the hawk fly att him, which (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Countrey, making songs upon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time.”

So Maponos, is the Divine Son, marked by matrilineal descent from the Divine Mother, musician and harper in his different aspects and Mabon – in Culhwch and Olwen, – is released from his dark dungeon to join the hunt for Twrch Trwyth and so takes from the King of boars one of the tokens from between his ears which is required for Culhwch to wed Olwen. The giant, Olwen’s father, says that the hunt for the boar cannot take place without him, and so neither can the wedding of Culhwch (himself a type of the divine boy coming of age) to Olwen (herself a type of the divine girl who awaits him). These two also grow into the light of life. So it is Maponos at Midsummer when the Sun rides high who both partakes in and blesses the wedding feast, the Master Magician fluidly inhabiting both roles. Such is the nature of myth. It’s not that he is, or he isn’t a Sun God; not that he is or he isn’t a Vegetation God … and though he is certainly the god that plays the sweetest tune, he doesn’t ask us to judge but to listen and to learn. The story that Apollo and Pan had a competition as to who was the better musician, a context won by Apollo, has been represented as the god competing with his older self. The Irish writer James Stephens made good use of this idea in his novel The Crock of Gold, in which Pan comes to Ireland and competes with Aengus Og. There is something fundamental here in the opposition of the Woodland Piper with the Muse of Song ; of the Hunter with his arrows and the Spirit of Poetry with his lyre; of the God of the Wild Places with the Master of the Revels. Maponos encompasses them all. He is the Awen, the spirit of Summer, youth transforming itself to awareness and remaining ever young, the inspiration and the expiration of the Muse and he plays his music in what seems like an endless day. His speech is not prose, but poetry; the sense of his song is the Summer

HYMN TO MAPONOS AT MIDSUMMER

|

The sun sails high in a neverdark sky

And Maponos rides the tide of summer Tall are the grasses grown in the fields the Breeze sighs through them, singing of summer The forests adorned with a crown of green beneath plays the God, in the glades of summer The harp of Maponos vibrates the air, and late, in the twilight, still it’s summer |

It often seems that each god has an alter ego, even an antithesis. Like so many gods the nature of Maponos is diverse. So he might also be called upon as here on a Gaulish tablet found in a sacred spring at Chamelières whose words are difficult to translate but might be rendered as

Maponos of the deep, great god

I come to thee with this plea:

Bring the spirits of the Otherworld

To inspire us who are before thee.

I come to thee with this plea:

Bring the spirits of the Otherworld

To inspire us who are before thee.

Perhaps we could consider the implications of a call to Maponos in this way as, apparently, a guide at the portal to the Underworld/Otherworld,functioning here, as the Romans saw him, in the way Apollo is seen as the patron of the Sybil as prophetess and guardian of the Portal and voice of the spirits. Asking him, then, for aid in calling on the powers of the Otherworld would seem to be an appropriate link with his embodiment as the Muse of prophecy and of inspiration as with the awenyddion of more recent Welsh tradition. So as he is here in the light of Midsummer so he also shows another side of his character facing the shade of the Portal from the nodal opposite of the other Solstice at which his mother, Matrona, brings light from the darkness.

What Arthur and his men enacted by violence and attack at Caer Loyw (a name which might also be construed as ‘the shining fortress’) – though with the more subtle help of the most ancient animals of the world – was simply a gesture in their world to a most ancient release of light from darkness that reaches its apogee now with the near perpetual daylight of Midsummer in the Brythonic lands.

The text in Gaulish of the PRAYER TO MAPONOS together with a tentative word for word translation is given in The Celtic Heroic Age eds John T Koch and John Carey (2003)

What Arthur and his men enacted by violence and attack at Caer Loyw (a name which might also be construed as ‘the shining fortress’) – though with the more subtle help of the most ancient animals of the world – was simply a gesture in their world to a most ancient release of light from darkness that reaches its apogee now with the near perpetual daylight of Midsummer in the Brythonic lands.

The text in Gaulish of the PRAYER TO MAPONOS together with a tentative word for word translation is given in The Celtic Heroic Age eds John T Koch and John Carey (2003)

Proudly powered by Weebly