Brython

Brythonic Polytheism in the Lancashire Landscape

by Lorna

An inspirited landscape. A landscape alive with spirits. Many cultures inhabit, and have inhabited, my locality of Penwortham, Lancashire, in North West England, and given names to its landmarks and deities. Whilst the predominant culture is English, there are strong traces of an earlier Brythonic culture and the Brythonic deities are still here.

Brythonic Culture

The name of the lost port off the coast of Fleetwood, Portus Setantiorum, ‘Port of the Setantii’, tells us that during the Roman period, the local Brythonic tribe were known as the Setantii, who John Porter describes as ‘the dwellers in the country of water’.

Evidence from the Riversway Dockfinds, including two dugout canoes, a bronze spearhead, the remains of a timber platform and human and animal remains suggests the Setantii inhabited a Lake Village here on Penwortham Marsh. Similar canoes have been found at Martin Mere and Marton Mere.

The earliest name for Penwortham in the Doomsday book is Peneverdant. Rev. Thornber claims it is of Brythonic origin: ‘pen, werd, or werid and want, as Caer Werid, the green city (Lancaster) and Derwent, the water, that is the green hill on the water.’

More recently, scholars have denounced ‘Peneverdant’ as a misspelling. It is generally agreed that ‘Pen’ is Brythonic and means ‘headland’, and that ‘wortham is Anglo-Saxon and means ‘settlement on the bend in the river’.

Ronald Cunliffe Shaw notes the existence of a chain of Brythonic and Anglicised Brythonic names ‘extending from the sites of the two ancient towers near Preston at Penwortham and Tulketh to Savock, Inskip, Treales, Bredekirk, Weeton (Weoh-dun‘sacred hill’), Preese, Rossall, and Bergerode.’ ‘Walton’ (in Walton-le-dale, east of Penwortham) translates as ‘town of the Welsh’, wahl being English for ‘foreigner’.

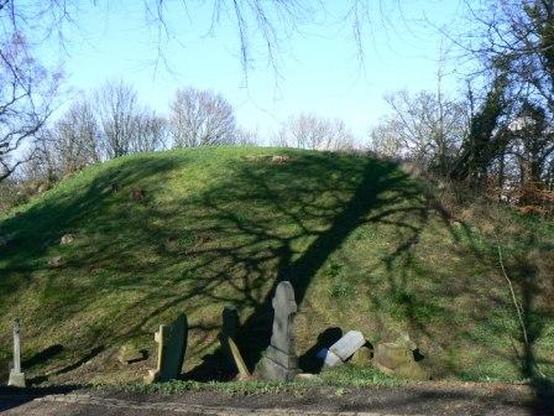

‘Pen’ refers to Castle Hill, where stood a Norman motte and bailey castle. As it is the first prominent landmark on the river Ribble, it seems likely the Britons used it as a defensive position. A Roman ballista ball and human skull (dated 60BC – 130AD) damaged by a weapon entering the mouth are suggestive of conflict between Britons and Romans during the Roman Invasion.

Castle Hill remains the seat of St Mary’s Church and a holy well dedicated to St Mary once poured forth its healing waters at its foot. Its prominence and healing springs would have marked its sanctity for the ‘pagan’ Britons.

It is unknown exactly when the people of present-day Lancashire converted to Christianity. Welsh poetry suggests that most of the rulers of northern Britain had adopted the new religion by the 6th century. Ronald Cunliffe Shaw argues that land-chapel sites, such as the one at Hutton, are suggestive of ‘an active British field church’.

The Battles of Chester (613), and of Maserfield (640) (which may have taken place in Winwick, in Makerfield) provide possible dates for when Anglo-Saxon settlement and acculturation of Cheshire and Lancashire began.

Denise Kenyon argues that earlier British lordships formed the basis for Anglo-Saxon territorial units. Penwortham may have formed part of ‘iuxta Rippel’, ‘a small British kingdom… encompassing the west Lancashire lowlands on either side of the Ribble, as far south as Makerfield, and extending into the Pennine foothills above Whalley.’

Whereas the ruling classes were Anglicised swiftly, rural people continued to speak Cumbric (the Brythonic language of Cumbria and Lancashire, which was similar to the Welsh Cymric), for much longer; this is evidenced by the ‘Yan Tan Tethera’ counting systems. Aidan Turner-Bishop links Lancashire’s ‘rich fairy and boggart tradition’ to scholarly suggestions that ‘fairies may be of Celtic origin, reflections of pagan Celtic spirits’.

Brythonic Culture

The name of the lost port off the coast of Fleetwood, Portus Setantiorum, ‘Port of the Setantii’, tells us that during the Roman period, the local Brythonic tribe were known as the Setantii, who John Porter describes as ‘the dwellers in the country of water’.

Evidence from the Riversway Dockfinds, including two dugout canoes, a bronze spearhead, the remains of a timber platform and human and animal remains suggests the Setantii inhabited a Lake Village here on Penwortham Marsh. Similar canoes have been found at Martin Mere and Marton Mere.

The earliest name for Penwortham in the Doomsday book is Peneverdant. Rev. Thornber claims it is of Brythonic origin: ‘pen, werd, or werid and want, as Caer Werid, the green city (Lancaster) and Derwent, the water, that is the green hill on the water.’

More recently, scholars have denounced ‘Peneverdant’ as a misspelling. It is generally agreed that ‘Pen’ is Brythonic and means ‘headland’, and that ‘wortham is Anglo-Saxon and means ‘settlement on the bend in the river’.

Ronald Cunliffe Shaw notes the existence of a chain of Brythonic and Anglicised Brythonic names ‘extending from the sites of the two ancient towers near Preston at Penwortham and Tulketh to Savock, Inskip, Treales, Bredekirk, Weeton (Weoh-dun‘sacred hill’), Preese, Rossall, and Bergerode.’ ‘Walton’ (in Walton-le-dale, east of Penwortham) translates as ‘town of the Welsh’, wahl being English for ‘foreigner’.

‘Pen’ refers to Castle Hill, where stood a Norman motte and bailey castle. As it is the first prominent landmark on the river Ribble, it seems likely the Britons used it as a defensive position. A Roman ballista ball and human skull (dated 60BC – 130AD) damaged by a weapon entering the mouth are suggestive of conflict between Britons and Romans during the Roman Invasion.

Castle Hill remains the seat of St Mary’s Church and a holy well dedicated to St Mary once poured forth its healing waters at its foot. Its prominence and healing springs would have marked its sanctity for the ‘pagan’ Britons.

It is unknown exactly when the people of present-day Lancashire converted to Christianity. Welsh poetry suggests that most of the rulers of northern Britain had adopted the new religion by the 6th century. Ronald Cunliffe Shaw argues that land-chapel sites, such as the one at Hutton, are suggestive of ‘an active British field church’.

The Battles of Chester (613), and of Maserfield (640) (which may have taken place in Winwick, in Makerfield) provide possible dates for when Anglo-Saxon settlement and acculturation of Cheshire and Lancashire began.

Denise Kenyon argues that earlier British lordships formed the basis for Anglo-Saxon territorial units. Penwortham may have formed part of ‘iuxta Rippel’, ‘a small British kingdom… encompassing the west Lancashire lowlands on either side of the Ribble, as far south as Makerfield, and extending into the Pennine foothills above Whalley.’

Whereas the ruling classes were Anglicised swiftly, rural people continued to speak Cumbric (the Brythonic language of Cumbria and Lancashire, which was similar to the Welsh Cymric), for much longer; this is evidenced by the ‘Yan Tan Tethera’ counting systems. Aidan Turner-Bishop links Lancashire’s ‘rich fairy and boggart tradition’ to scholarly suggestions that ‘fairies may be of Celtic origin, reflections of pagan Celtic spirits’.

Brythonic Deities

The dedication of the church on Castle Hill to St Mary the Virgin, the healing and cleansing properties of her well, and references to prayers addressed to Stella Maris, ‘Star of the Sea’, may allude to the presence of an earlier Brythonic goddess of motherhood and water.

Interestingly, the Welsh for sea is mor, while marian refers to liminal places. My locality has a particularly strong Marian heritage, with a proliferation of churches dedicated to both St Mary the Virgin and to St Mary Magdalene and numerous ‘Lady Wells’ (most but not all now dried up). Cockersand Abbey is dedicated to Mary of the Marsh. As Castle Hill was once surrounded by Penwortham Marsh, I wonder if this is ‘the same’ ‘Mary’.

There is lots of evidence in the area for cults of the Mothers. In the church of St John the Evangelist at Lund is a beautifully preserved altar featuring three mother goddesses on the front and three dancing figures on either side. It is aptly used as a baptismal font.

The sandstone of the altar has been dated to 2AD. It originates from upriver at Ribchester, during the time it was a Roman fort known as Bremetonnacum, ‘The Place on the Roaring Ford’. There are altars to Dea Matraonae, ‘The Mothers’, and to Apollo-Maponus.

Matrona means ‘Mother’ and Maponos ‘Son’ in Brythonic. They appear as Modron and Mabon in medieval Welsh literature. Mabon is rescued from a ‘house of stone’ by a band of men riding upriver on a salmon. This imagery evokes the birth of both son and sun from mother earth. I have often wondered whether ‘Mary’ is a face of Matrona/Modron.

Castle Hill also possesses a fascinating fairy funeral legend. This is located on the coffin path leading up Church Avenue to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church. Whilst the earliest known burial is said to be a Crusader, dating to the 12th century, it is my intuition that the castle mound was built over a burial mound; burial mounds are often equated with fairy mounds.

A pathway called Fairy Lane runs to the east of the hill and this is where I met Gwyn ap Nudd, a Brythonic Fairy King and ruler of Annwn and the dead. Could the ‘Pen’ in Penwortham also refer to Pen Annwn, ‘Head of the Otherworld’?

The dedication of the church on Castle Hill to St Mary the Virgin, the healing and cleansing properties of her well, and references to prayers addressed to Stella Maris, ‘Star of the Sea’, may allude to the presence of an earlier Brythonic goddess of motherhood and water.

Interestingly, the Welsh for sea is mor, while marian refers to liminal places. My locality has a particularly strong Marian heritage, with a proliferation of churches dedicated to both St Mary the Virgin and to St Mary Magdalene and numerous ‘Lady Wells’ (most but not all now dried up). Cockersand Abbey is dedicated to Mary of the Marsh. As Castle Hill was once surrounded by Penwortham Marsh, I wonder if this is ‘the same’ ‘Mary’.

There is lots of evidence in the area for cults of the Mothers. In the church of St John the Evangelist at Lund is a beautifully preserved altar featuring three mother goddesses on the front and three dancing figures on either side. It is aptly used as a baptismal font.

The sandstone of the altar has been dated to 2AD. It originates from upriver at Ribchester, during the time it was a Roman fort known as Bremetonnacum, ‘The Place on the Roaring Ford’. There are altars to Dea Matraonae, ‘The Mothers’, and to Apollo-Maponus.

Matrona means ‘Mother’ and Maponos ‘Son’ in Brythonic. They appear as Modron and Mabon in medieval Welsh literature. Mabon is rescued from a ‘house of stone’ by a band of men riding upriver on a salmon. This imagery evokes the birth of both son and sun from mother earth. I have often wondered whether ‘Mary’ is a face of Matrona/Modron.

Castle Hill also possesses a fascinating fairy funeral legend. This is located on the coffin path leading up Church Avenue to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church. Whilst the earliest known burial is said to be a Crusader, dating to the 12th century, it is my intuition that the castle mound was built over a burial mound; burial mounds are often equated with fairy mounds.

A pathway called Fairy Lane runs to the east of the hill and this is where I met Gwyn ap Nudd, a Brythonic Fairy King and ruler of Annwn and the dead. Could the ‘Pen’ in Penwortham also refer to Pen Annwn, ‘Head of the Otherworld’?

|

In his Geography (2AD), Ptolemy refers to the estuary of the Ribble as Belisama Aest. Here we find the name of the goddess of the Ribble, Reigh Belisama. Her name is Gallo-Brythonic and means ‘Most Shining Queen’ or ‘Most Mighty Queen’. Many complex and convoluted theories have been put forward to explain how the Ribble got its name. My answer is that Reigh Belisama simply got shortened to Ri-bel.

Belisama’s river and its tributaries shape my landscape, carving its valleys, providing nurturing water to its inhabitants. The Ribble is tidal at Penwortham. At low tides we see Belisama’s shining nature; sparkling waters, glinting fay-lights. At high tides we experience her might. This was no more apparent than last year, when the Ribble burst its banks and flooded Avenham Park. |

The Ribble Estuary is renowned as the UK’s most important site for over-wintering birds. In my area alone it’s possible to see teal, widgeon, and pintail, alongside residents such as mallards, goosander, lapwings, cormorants and mute swans. In the summer, common terns nest on Riversway Dockland and swallows swoop and soar over the waters.

Belisama watches over this remarkable ecosystem, sometimes as a bright lady veiled in sunshine, sometimes as a murky sprite swimming through the muddy tides and treading without trace on the treacherous sands. One of the darker legends associated with the Ribble is that it takes a life every seven years.

On Cockersand Moss, two silver statuettes dedicated to Nodens, ‘the Catcher’ were found. He is a Brythonic god of hunting, healing, water, weather, and dreams, best known for the remains of his temple at Lydney, Gloucestershire. Scholars have suggested a similar structure may have existed in Lancashire, but it has never been found. It is my suspicion that, like Portus Setantiorum, Thornton Cleveleys (and, soon, Cockersand Abbey), it is submerged beneath the sea. The statues may have been dropped by refugees escaping the deluge.

Lune Estuary from nr Cockersand Abbey, Nodens weatherIn medieval Welsh literature, Nodens appears as Nudd/Lludd Llaw Eraint. Nodens/Nudd’s presence in within the landscape backs up my intuition that his son, Gwyn, also has connections with my locality.

There are other deities whose presence I have experienced within my landscape who have not provided names, such as the water dragon who was the spirit of the aquifer beneath Castle Hill before it was shattered and now exists as a ghost. The local spirits have given me names with a variety of linguistic origins.

Brythonic polytheism also has an animistic core, acknowledging each tree, plant, animal, bird, insect, and rock as an inspirited being. This is illustrated by the Welsh myths, where humans speak to the Oldest Animals: a blackbird, a stag, an owl, an eagle and a salmon, and are capable of shapeshifting. Such stories inform our relationships with the creatures of our living landscapes and our shamanistic practices.

Living in relationship with the land, its deities and its human and other-than-human inhabitants brings responsibilities, such as picking up litter from the area one cares for and protesting against unwanted developments such as fracking. My personal calling as an awenydd includes these things and passing on the stories of the land and its deities through written and spoken words.

SOURCES

Denise Kenyon, The Origins of Lancashire, (Manchester University Press, 1991)

John Porter, History of the Fylde, (Biblibazaar, 2009)

Linda Sever (ed), Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, (History Press, 2010)

Rev. W. Thornber, The Castle Hill of Penwortham, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, 1856/7

Ronald Cunliffe Shaw, Men of the North, (Leyland Printing, 1970)

Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, (OUP Oxford, 2008)

Cockersand Moss Temple, Roman Britain

Belisama watches over this remarkable ecosystem, sometimes as a bright lady veiled in sunshine, sometimes as a murky sprite swimming through the muddy tides and treading without trace on the treacherous sands. One of the darker legends associated with the Ribble is that it takes a life every seven years.

On Cockersand Moss, two silver statuettes dedicated to Nodens, ‘the Catcher’ were found. He is a Brythonic god of hunting, healing, water, weather, and dreams, best known for the remains of his temple at Lydney, Gloucestershire. Scholars have suggested a similar structure may have existed in Lancashire, but it has never been found. It is my suspicion that, like Portus Setantiorum, Thornton Cleveleys (and, soon, Cockersand Abbey), it is submerged beneath the sea. The statues may have been dropped by refugees escaping the deluge.

Lune Estuary from nr Cockersand Abbey, Nodens weatherIn medieval Welsh literature, Nodens appears as Nudd/Lludd Llaw Eraint. Nodens/Nudd’s presence in within the landscape backs up my intuition that his son, Gwyn, also has connections with my locality.

There are other deities whose presence I have experienced within my landscape who have not provided names, such as the water dragon who was the spirit of the aquifer beneath Castle Hill before it was shattered and now exists as a ghost. The local spirits have given me names with a variety of linguistic origins.

Brythonic polytheism also has an animistic core, acknowledging each tree, plant, animal, bird, insect, and rock as an inspirited being. This is illustrated by the Welsh myths, where humans speak to the Oldest Animals: a blackbird, a stag, an owl, an eagle and a salmon, and are capable of shapeshifting. Such stories inform our relationships with the creatures of our living landscapes and our shamanistic practices.

Living in relationship with the land, its deities and its human and other-than-human inhabitants brings responsibilities, such as picking up litter from the area one cares for and protesting against unwanted developments such as fracking. My personal calling as an awenydd includes these things and passing on the stories of the land and its deities through written and spoken words.

SOURCES

Denise Kenyon, The Origins of Lancashire, (Manchester University Press, 1991)

John Porter, History of the Fylde, (Biblibazaar, 2009)

Linda Sever (ed), Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, (History Press, 2010)

Rev. W. Thornber, The Castle Hill of Penwortham, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, 1856/7

Ronald Cunliffe Shaw, Men of the North, (Leyland Printing, 1970)

Sioned Davies, The Mabinogion, (OUP Oxford, 2008)

Cockersand Moss Temple, Roman Britain

Proudly powered by Weebly