Brython

Nos Galan Gaeaf - 31st October

Nos Galan Gaeaf is an ysbrydnos (spirit night) and the pivotal point when the powers of darkness and winter return to this world with the spirits of the dead. It is a time for honouring our ancestors, particularly those who have passed in the last year. This was traditionally a night when glimpses of the future could be seen hence some of us practice divination.

Gwyn’s Hunt

Festival honouring Gwyn as he rides out with the huntsmen and hounds and Annwn to gather the souls of the dead.

First Dark Moon: Rhiannon’s return to Annwn

A festival acknowledging Rhiannon’s return from thisworld to Annwn celebrating her role as psychopomp.

Festival honouring Gwyn as he rides out with the huntsmen and hounds and Annwn to gather the souls of the dead.

First Dark Moon: Rhiannon’s return to Annwn

A festival acknowledging Rhiannon’s return from thisworld to Annwn celebrating her role as psychopomp.

Traditional Customs for the Calend of Winter

Many of the seasonal customs recorded in rural communities have their roots in stories and folklore well established for generations before they took the shapes identified in those recording them. Some may go back to even older observances with mythological origins.

The coming of winter, or Calan Gaeaf, is resonant with tales and images that reflect deeply embedded responses to the shortening days and the coming of the longer, darker, nights. We are all familiar with the modern practices of ‘trick or treat’ at ‘Hallowe’en’ and the associated paraphernalia of ghoul masks and scary images. Older customs were less eager to engage so familiarly with the darker denizens of the night, or at least preferred to do so with more respect than is shown by modern revellers. There was, however, a custom of calling at houses asking for food on behalf of the ‘messengers of the dead’. No tricks here but some bread, cheese and apples were a welcome treat.

Apparently benign customs such as apple bobbing provided the amusement of watching people trying to eat apples floating in tubs of water or dangling from strings without using their hands. Bonfires were lit and while they burned food could be cooked or nuts thrown into the flames for the purposes of making predictions from the way they burned. But as the fires burned low and gradually went out, more serious divinations might be attempted from the ashes as the dark closed in.

It was on the way home from such bonfire events that the sort of spirits represented by the modern ghoul masks might be encountered. But they were to be avoided rather than imitated. On such a night the Cwn Annwn might be encountered. These are familiar to readers of the Mabinogi stories as the red-eared hounds of the otherworld king Arawn. But their appearance on the folklore tradition is often much more sinister. They are variously described, but their red ears often have an eerie glow and they sometimes also have fire-red eyes. Marie Trevelyan describes them as follows:

Sometimes they travelled in weird packs alone, but frequently they were guided by their master. He is described as a dark, almost black, gigantic figure, with a horn slung around his swarthy neck, and a long hunting-pole at his back….. sometimes with a creature half wolf / half dog with him. There too is the Brenin Llwyd or Grey King with the Cŵn Wybyr, or Dogs of the Sky, in his court of mist.

Here, although he is not named, is a memory of Gwyn ap Nudd in different guises slipping through the mist between the worlds, his hounds held in check as it is said in the medieval Welsh tale Culhwch and Olwen that he ‘contains the essence of the devils of Annwn in him, lest this world be destroyed’. Such devils are not to be held up as figures of fun, but treated with respect, as they surely would have been by those coming home from the Calan Gaeaf bonfires.

Another creature they might have feared is the Hwch Ddu Gwta (Black Short-tailed Sow), an otherworld pig who it was said emerged from the bonfire ash and then waited at stiles for those walking home late from the festivities. She is remembered in this old Welsh nursery rhyme:

The coming of winter, or Calan Gaeaf, is resonant with tales and images that reflect deeply embedded responses to the shortening days and the coming of the longer, darker, nights. We are all familiar with the modern practices of ‘trick or treat’ at ‘Hallowe’en’ and the associated paraphernalia of ghoul masks and scary images. Older customs were less eager to engage so familiarly with the darker denizens of the night, or at least preferred to do so with more respect than is shown by modern revellers. There was, however, a custom of calling at houses asking for food on behalf of the ‘messengers of the dead’. No tricks here but some bread, cheese and apples were a welcome treat.

Apparently benign customs such as apple bobbing provided the amusement of watching people trying to eat apples floating in tubs of water or dangling from strings without using their hands. Bonfires were lit and while they burned food could be cooked or nuts thrown into the flames for the purposes of making predictions from the way they burned. But as the fires burned low and gradually went out, more serious divinations might be attempted from the ashes as the dark closed in.

It was on the way home from such bonfire events that the sort of spirits represented by the modern ghoul masks might be encountered. But they were to be avoided rather than imitated. On such a night the Cwn Annwn might be encountered. These are familiar to readers of the Mabinogi stories as the red-eared hounds of the otherworld king Arawn. But their appearance on the folklore tradition is often much more sinister. They are variously described, but their red ears often have an eerie glow and they sometimes also have fire-red eyes. Marie Trevelyan describes them as follows:

Sometimes they travelled in weird packs alone, but frequently they were guided by their master. He is described as a dark, almost black, gigantic figure, with a horn slung around his swarthy neck, and a long hunting-pole at his back….. sometimes with a creature half wolf / half dog with him. There too is the Brenin Llwyd or Grey King with the Cŵn Wybyr, or Dogs of the Sky, in his court of mist.

Here, although he is not named, is a memory of Gwyn ap Nudd in different guises slipping through the mist between the worlds, his hounds held in check as it is said in the medieval Welsh tale Culhwch and Olwen that he ‘contains the essence of the devils of Annwn in him, lest this world be destroyed’. Such devils are not to be held up as figures of fun, but treated with respect, as they surely would have been by those coming home from the Calan Gaeaf bonfires.

Another creature they might have feared is the Hwch Ddu Gwta (Black Short-tailed Sow), an otherworld pig who it was said emerged from the bonfire ash and then waited at stiles for those walking home late from the festivities. She is remembered in this old Welsh nursery rhyme:

Hwch Ddu Gwta

Ar bob camfa

Yn nyddu a cardio

Bob Nos Glangaea

…

Adre, adre, am y cynta

Hwch Dddu Gwta gipio’r ola.

Black short-tailed sow

On every stile

Spinning and weaving

On Calan Gaeaf night

…

Get home quick, be the first

The Hwch Ddu Gwta gets the last.

Ar bob camfa

Yn nyddu a cardio

Bob Nos Glangaea

…

Adre, adre, am y cynta

Hwch Dddu Gwta gipio’r ola.

Black short-tailed sow

On every stile

Spinning and weaving

On Calan Gaeaf night

…

Get home quick, be the first

The Hwch Ddu Gwta gets the last.

Who spins and weaves by stiles on such a night? Perhaps the ‘Ladi Wen’ (White Lady) another spirit who was said to be abroad at Calan Gaeaf, and who might she be but Ceridwen, mother of Afagddu (‘Deep Dark’), keeper of the cauldron from which Taliesin gained inspiration and acknowledged by the early medieval Welsh bards as the source of their awen. But she is perilous. Like the Cailleach of Irish and Scottish tradition she is the wise crone but also the Hag of Winter, embodying the very darkness itself as winter falls. Her name is ambiguous, with the possible range of ‘crooked hag’ , ‘woman who brings fever’, ‘passionate one’. As well as the mother of Afagddu she also has a daughter Creirwy (‘living treasure’) who was ‘the fairest maiden in the world’, and whose name might might be related to Ceridwen’s own name. Here we have the hag who becomes a young woman when kissed by a chosen suitor, common in folklore and in medieval literature. So she is the mother both of darkness and of all that is fair. Her cauldron is the cauldron of unmaking, the darkness which must be embraced if rebirth is to be possible. Her withered lips that must be kissed set the seal on winter and the potential of the far-off spring. She contains all in her cauldron.

This is the parable of Calan Gaeaf, of Winterfall, of the Grey Mari (who appears later in the winter festivals as the ghostly horse’s head of the Mari Lwyd customs), of the Black Sow, of the Mother of Darkness who brings the night out of her cauldron and from which the season can be re-born if the devils of Annwn can be contained by the Lord of the Otherworld in the Kingdom of Mist; but we must bide the time for this to be so and not deny them in either trick or treat as they flit through the dark , but keep the season with them, and for them, as they pass.

REFERENCES

Marie Trevelyan Folklore and Folk Stories of Wales (1909).

T. Gwynn Jones Welsh Folklore and Folk Custom (1930)

Trefor M Owen Welsh Folklore and Custom (National Museum of Wales, 1959)

This is the parable of Calan Gaeaf, of Winterfall, of the Grey Mari (who appears later in the winter festivals as the ghostly horse’s head of the Mari Lwyd customs), of the Black Sow, of the Mother of Darkness who brings the night out of her cauldron and from which the season can be re-born if the devils of Annwn can be contained by the Lord of the Otherworld in the Kingdom of Mist; but we must bide the time for this to be so and not deny them in either trick or treat as they flit through the dark , but keep the season with them, and for them, as they pass.

REFERENCES

Marie Trevelyan Folklore and Folk Stories of Wales (1909).

T. Gwynn Jones Welsh Folklore and Folk Custom (1930)

Trefor M Owen Welsh Folklore and Custom (National Museum of Wales, 1959)

Gwyn's Hunt

by Lorna

Within Neo-Paganism Gwyn ap Nudd is generally understood to be a leader of ‘the Wild Hunt’. Before Jacob Grimm developed ‘the Wild Hunt’ as a concept applied to various otherworldly hunts across Europe in his Deutsch Mythologie (1835), they were known by individual names often referring to their leaders such as ‘Woden’s Hunt’, ‘Household of Harlequin’, and ‘Herla’s Assembly’. This essay will focus on the Brythonic tradition of ‘Gwyn’s Hunt’.

The earliest literary reference to Gwyn as a hunter comes from Culhwch and Olwen (1090) where it is stated, ‘Twrch Trwyth will not be hunted until Gwyn son of Nudd is found.’ This suggests Gwyn was the leader of the hunt for Twrch Trwyth, ‘King of Boars’, prior to Arthur. According to the text, which was penned by Christian scribes, Twrch Trwyth was a king changed into a swine by God ‘for his sins’. This overlay conceals a pagan tradition wherein the ‘boar’ was a human shapeshifter. Gwyn’s hunt was for a man: a shapeshifting human soul.

The following lines, ‘God has put the fury of the devils of Annwn in him, lest the world be destroyed. He will not be spared from there’ form another Christian overlay obscuring Gwyn’s role as a protector and ruler of Annwn containing furious spirits including the fay and the dead within his realm and person. The comb, razor, and shears Twrch Trwyth mysteriously carries between his ears may have been grave goods, suggesting he is a restless soul Gwyn hunts down into the ocean (symbolic of Annwn ‘the Deep’) on a cyclical basis to lay to rest.

In later folklore Gwyn is depicted hunting for souls with the Cwn Annwn, ‘Hounds of the Otherworld’, who are also known as Cwn Wybyr, ‘Hounds of the Sky’, and Cwn Cyrff, ‘Corpse Dogs’. These include Dormach, ‘Death’s Door’, Gwyn’s fair red-nosed hunting dog. To hear or see the Cwn Annwn is a portent of death. This belief may be rooted in earlier traditions where wolves and dogs along with carrion birds (Gwyn is also associated with ravens who ‘croak over blood’) devoured the corpses of the dead before Gwyn gathered their souls.

A fascinating legend surrounds the minstrel Ned Pugh or Iolo ap Huw who disappeared into the cave of Tag y Clegyr playing ‘Ffarwel Ned Pugh’, ‘Ned Pugh’s Farewell’:

‘To leave my dear girl, my country, and friends,

and roam o’er the ocean, where toil never ends;

to mount the high yards, when the whistle shall sound,

Amidst the wild winds as they bluster around!’

Exchanging ‘his fiddle for a bugle’ the minstrel became Gwyn’s huntsman-in-chief and can be found ‘cheering Cwn Annwn over Cader Idris’ every Nos Galan Gaeaf.

The earliest literary reference to Gwyn as a hunter comes from Culhwch and Olwen (1090) where it is stated, ‘Twrch Trwyth will not be hunted until Gwyn son of Nudd is found.’ This suggests Gwyn was the leader of the hunt for Twrch Trwyth, ‘King of Boars’, prior to Arthur. According to the text, which was penned by Christian scribes, Twrch Trwyth was a king changed into a swine by God ‘for his sins’. This overlay conceals a pagan tradition wherein the ‘boar’ was a human shapeshifter. Gwyn’s hunt was for a man: a shapeshifting human soul.

The following lines, ‘God has put the fury of the devils of Annwn in him, lest the world be destroyed. He will not be spared from there’ form another Christian overlay obscuring Gwyn’s role as a protector and ruler of Annwn containing furious spirits including the fay and the dead within his realm and person. The comb, razor, and shears Twrch Trwyth mysteriously carries between his ears may have been grave goods, suggesting he is a restless soul Gwyn hunts down into the ocean (symbolic of Annwn ‘the Deep’) on a cyclical basis to lay to rest.

In later folklore Gwyn is depicted hunting for souls with the Cwn Annwn, ‘Hounds of the Otherworld’, who are also known as Cwn Wybyr, ‘Hounds of the Sky’, and Cwn Cyrff, ‘Corpse Dogs’. These include Dormach, ‘Death’s Door’, Gwyn’s fair red-nosed hunting dog. To hear or see the Cwn Annwn is a portent of death. This belief may be rooted in earlier traditions where wolves and dogs along with carrion birds (Gwyn is also associated with ravens who ‘croak over blood’) devoured the corpses of the dead before Gwyn gathered their souls.

A fascinating legend surrounds the minstrel Ned Pugh or Iolo ap Huw who disappeared into the cave of Tag y Clegyr playing ‘Ffarwel Ned Pugh’, ‘Ned Pugh’s Farewell’:

‘To leave my dear girl, my country, and friends,

and roam o’er the ocean, where toil never ends;

to mount the high yards, when the whistle shall sound,

Amidst the wild winds as they bluster around!’

Exchanging ‘his fiddle for a bugle’ the minstrel became Gwyn’s huntsman-in-chief and can be found ‘cheering Cwn Annwn over Cader Idris’ every Nos Galan Gaeaf.

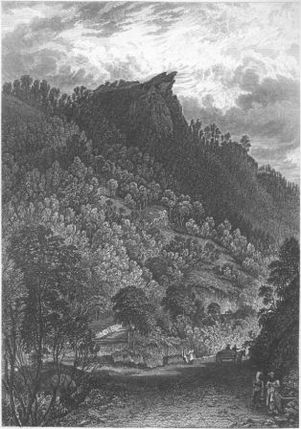

Cadair Idris & Eagle's Crag

There are numerous instances where Gwyn (by this name or as a spectral or demon huntsman or fairy king), sometimes with his hunt and sometimes alone, also carries off the souls of the living. On Nos Galan Gaeaf, Gwyn wins back his beloved, Creiddylad, from Gwythyr and takes her to Annwn. Creiddylad’s descent with Gwyn to the underworld explains the coming of winter. Later tales of abduction may have some basis in this old seasonal myth.

Here, on the borders of Lancashire and Yorkshire, there is a story featuring Sybil, the Lady of Bearnshaw Tower, who spends an unseemly amount of time on the hills and moors chasing wild swans whose hound-like calls remind her of ‘wild hunters and the spectral horseman’. She is swept from the dizzy heights of Eagle Crag overlooking Cliviger Gorge by a ‘demon’:

‘Immediately she felt as though she were sweeping through the trackless air... she thought the whole world lay at her feet, and the kingdoms of the earth moved on like a mighty pageant. Then did the vision change. Objects began to waver and grow dim, as if passing through a mist; and she found herself again upon that lonely crag, and her conductor at her side.’

Gwyn ap Nudd, ‘White son of Mist’, goes ‘between sky and air’ and moves ar wybir ‘through the clouds’. I believe Gwyn is ‘the spectral horseman’ and Sybil’s demonic ‘conductor’.

Sybil’s ability to shapeshift may have been learnt from Gwyn: a god of transformation. In deer-form she is hunted down by a human huntsman called William Towneley and forced to marry him. Her failed attempt to escape in cat-form leads to her death and burial at Eagle’s Crag where she was captured; her ghost and William’s can be seen there every Nos Galan Gaeaf.

The Cliviger area is also haunted by Gabriel Ratchets, corpse hounds who may be an Anglicised variant of the Cwn Annwn. In his poem, ‘Gabriel Ratchets’, which is based on Sybil’s story, Philip Hamerton opens: ‘Wild huntsmen? ‘Twas a flight of swans / But how invisibly they flew.’

Gwyn and his hunt are associated with soul flight and ecstasis. Ecstatic experiences with otherworldly beings were frowned upon by the Christian church and twisted into stories of abduction by a demon huntsman or fairy king who was confronted by knights and heroes who won those ‘poor souls’ back (whether they wanted to return or not...).

When I accepted Gwyn’s challenge to ride with him to the Otherworld and offered my soul into his care he showed me parts of Lancashire where people lived in lake villages and walked on wooden trackways then glaciers creeping across the landscape with blizzard winds.

This has led me to believe Gwyn was worshiped as a god of hunting and the transitions of the souls of the dead and living between worlds by this land’s earliest inhabitants after the Ice Age. Yuri Leitch identifies Gwyn with the constellation of Orion and Dormach with Canis Major (Sirius, the dog star is Dormach’s red nose). Gwyn is our ancient British Hunter in the Skies who rises from Annwn on Nos Galan Gaeaf and presides over the dark months of winter.

Nos Galan Gaeaf is an ysbrydnos ‘spirit night’ when Gwyn’s Hunt rides and the borders between thisworld and Annwn, life and death, and the laws that govern time and space break down. It is a time of migrating swans and geese and transitions of souls. It is a time of deep magic.

I’ll end with a passage from Sian Hayton’s ‘The Story of Kigva’ because it evokes for me so beautifully the experience of flying with Gwyn:

‘She felt a hand on her arm... steady, comforting her in her despair. The strongest one of all was there, as he had been in the forest and he promised, silently, that he would stay with her for the rest of her vigil. With tears she thanked him and felt herself gathered up in his arms. Together, from then on, they wandered the universe. He showed her things which only he knew. With him she touched the cold, hard moon and walked on the black rind of the sky. She found the stars felt like the taste of blaeberries and the north wind was truly a great river whose source was the mountains of the sun. He gave her jewelled collars and crowns and broke open an oak-tree so that she could feast on the honey. There was no one equal to him.’

Here, on the borders of Lancashire and Yorkshire, there is a story featuring Sybil, the Lady of Bearnshaw Tower, who spends an unseemly amount of time on the hills and moors chasing wild swans whose hound-like calls remind her of ‘wild hunters and the spectral horseman’. She is swept from the dizzy heights of Eagle Crag overlooking Cliviger Gorge by a ‘demon’:

‘Immediately she felt as though she were sweeping through the trackless air... she thought the whole world lay at her feet, and the kingdoms of the earth moved on like a mighty pageant. Then did the vision change. Objects began to waver and grow dim, as if passing through a mist; and she found herself again upon that lonely crag, and her conductor at her side.’

Gwyn ap Nudd, ‘White son of Mist’, goes ‘between sky and air’ and moves ar wybir ‘through the clouds’. I believe Gwyn is ‘the spectral horseman’ and Sybil’s demonic ‘conductor’.

Sybil’s ability to shapeshift may have been learnt from Gwyn: a god of transformation. In deer-form she is hunted down by a human huntsman called William Towneley and forced to marry him. Her failed attempt to escape in cat-form leads to her death and burial at Eagle’s Crag where she was captured; her ghost and William’s can be seen there every Nos Galan Gaeaf.

The Cliviger area is also haunted by Gabriel Ratchets, corpse hounds who may be an Anglicised variant of the Cwn Annwn. In his poem, ‘Gabriel Ratchets’, which is based on Sybil’s story, Philip Hamerton opens: ‘Wild huntsmen? ‘Twas a flight of swans / But how invisibly they flew.’

Gwyn and his hunt are associated with soul flight and ecstasis. Ecstatic experiences with otherworldly beings were frowned upon by the Christian church and twisted into stories of abduction by a demon huntsman or fairy king who was confronted by knights and heroes who won those ‘poor souls’ back (whether they wanted to return or not...).

When I accepted Gwyn’s challenge to ride with him to the Otherworld and offered my soul into his care he showed me parts of Lancashire where people lived in lake villages and walked on wooden trackways then glaciers creeping across the landscape with blizzard winds.

This has led me to believe Gwyn was worshiped as a god of hunting and the transitions of the souls of the dead and living between worlds by this land’s earliest inhabitants after the Ice Age. Yuri Leitch identifies Gwyn with the constellation of Orion and Dormach with Canis Major (Sirius, the dog star is Dormach’s red nose). Gwyn is our ancient British Hunter in the Skies who rises from Annwn on Nos Galan Gaeaf and presides over the dark months of winter.

Nos Galan Gaeaf is an ysbrydnos ‘spirit night’ when Gwyn’s Hunt rides and the borders between thisworld and Annwn, life and death, and the laws that govern time and space break down. It is a time of migrating swans and geese and transitions of souls. It is a time of deep magic.

I’ll end with a passage from Sian Hayton’s ‘The Story of Kigva’ because it evokes for me so beautifully the experience of flying with Gwyn:

‘She felt a hand on her arm... steady, comforting her in her despair. The strongest one of all was there, as he had been in the forest and he promised, silently, that he would stay with her for the rest of her vigil. With tears she thanked him and felt herself gathered up in his arms. Together, from then on, they wandered the universe. He showed her things which only he knew. With him she touched the cold, hard moon and walked on the black rind of the sky. She found the stars felt like the taste of blaeberries and the north wind was truly a great river whose source was the mountains of the sun. He gave her jewelled collars and crowns and broke open an oak-tree so that she could feast on the honey. There was no one equal to him.’

Proudly powered by Weebly